OVERVIEW

The term Hip Arthroscopy (or ‘keyhole’ surgery) refers to the viewing of the inside of a joint through a small operating telescope.

First described in the 1970s, arthroscopic techniques have become an increasingly popular method of treating conditions around the hip. This is mainly due to the recent identification of pathological conditions such as femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and associated labral tears. In recent years, however, this technique has been used to help in the treatment of many other joint pathologies, and has gained popularity because of the small incisions used and improved recovery times when compared with conventional ‘open’ surgery.

The other advantages of arthroscopic versus open surgery are decreased blood loss, faster recovery periods and less pain. Hip arthroscopy can also be performed as a day-case procedure (i.e. no need to stay in hospital overnight).

ANATOMY

The hip is functionally a ball and socket joint. (See figure 1). It consists of the head of the femur (the ball) and the acetabulum (the socket). Both the ball and socket are covered with articular cartilage, which allows smooth, almost frictionless gliding between the two surfaces. The edge of the acetabulum is surrounded by a fibrous structure that envelops the femoral head, the ‘labrum’. The labrum acts as a seal, or gasket, around the femoral head.

However, this is not its only function, as it has been shown to contain nerve endings, and therefore may be painful if damaged. A total of 27 muscles cross the hip joint, making it a very deep part of the body for arthroscopic access. This is one reason why hip arthroscopy can be technically demanding.

TECHNIQUE OF HIP ARTHROSCOPY

The procedure is usually performed with the patient asleep (general anaesthetic). There are two widely used methods, one with the patient on their back (supine) and the other on their side (lateral decubitus). Which is used is down to the surgeon’s preference. To gain access to the central compartment of the hip joint (between the ball and socket), traction is applied to the affected leg after placing the foot into a special boot. This causes a small space to open between the ball and socket allowing the introduction of the arthroscope.

Once the first portal is correctly placed, any further portals may be created once the camera is in position, to ensure that they are placed with minimal risk to the joint surfaces. This process can be repeated to gain as many points of entry to the hip joint as the surgeon requires, normally between two and four. The time needed for a hip arthroscopy is usually around 80 to 90 minutes, although this can vary depending on the specifics of each case. The leg is not needed to be in traction for all of this time, minimising the risk of nerve bruising.

INDICATIONS

Hip arthroscopy was initially used for the diagnosis of unexplained hip pain, but is now widely used in the treatment of conditions both in and outside the hip joint itself. The most common indication currently is for the treatment of FAI and its associated pathologies.

CAM-TYPE FEMOROACETABULAR IMPINGEMENT

Cam impingement is created by the abnormal development of the femoral head-neck junction. This type of deformity is characterised by varying amounts of abnormal bone on the anterior and superior femoral neck. A bony protrusion or bump has been likened to a cam, an eccentric part of a rotating device. This leads to joint damage as a result of the non-spherical femoral head being forced into the acetabulum, mainly with flexion and/or internal rotation. This may impart compression and shear forces to the articular cartilage, and may lead to labral tears and peeling away of the articular cartilage from the underlying bone, leading to early arthritis. Standard arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic cam FAI involves resection or repair of any labral and chondral injuries, and subsequent reshaping of the head-neck junction of the upper femur using high-speed motorised burrs.

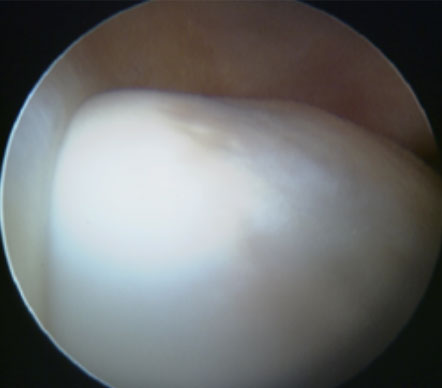

CAM

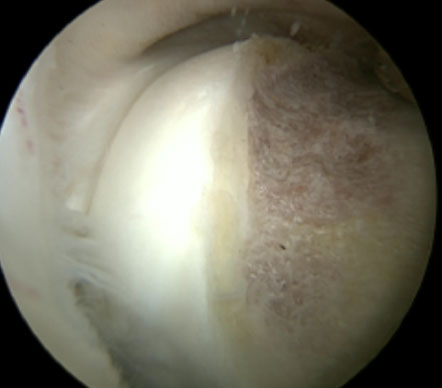

CAM RESECTION

PINCER-TYPE FEMOROACETABULAR IMPINGEMENT

In contrast, pincer impingement is a result of an abnormality on the acetabular side of the hip joint. The acetabulum may either have a more posterior orientation than normal, otherwise known as acetabular retroversion, or there may be extra bone around the rim. This results in contact of the femoral neck against the labrum and rim of the acetabulum during hip movement earlier than might otherwise be the case. Repeated contact between the femoral neck and the edge of the acetabulum may lead to damage to the labrum and adjacent articular cartilage. Bone formation, or ossification within the labrum may be commonly seen as a result of this repeated contact. It is thought that this type of impingement may also predispose to the development of osteoarthritis. The goal of the arthroscopic treatment of pincer impingement is to reduce the acetabular over coverage of the hip. Methods to reduce this over coverage of the ball by the socket include labral detachment, acetabular rim recession using burrs, often reattaching the labrum with anchors at the end of the procedure.

LABRAL REPAIR

The acetabular labrum is a fibrous structure, which surrounds the femoral head. It forms a seal to the hip joint, and is an important adjunct to the lubrication of the joint. The labrum also has a nerve supply and may cause pain if damaged. The underside of the labrum is continuous with the acetabular articular cartilage so any compressive forces that affect the labrum may also cause articular cartilage damage, particularly at the junction between the two, the chondrolabral junction. The labrum may be damaged or torn as part of an underlying process, such as FAI or dysplasia (shallow hip socket), or may be injured directly by a traumatic event.

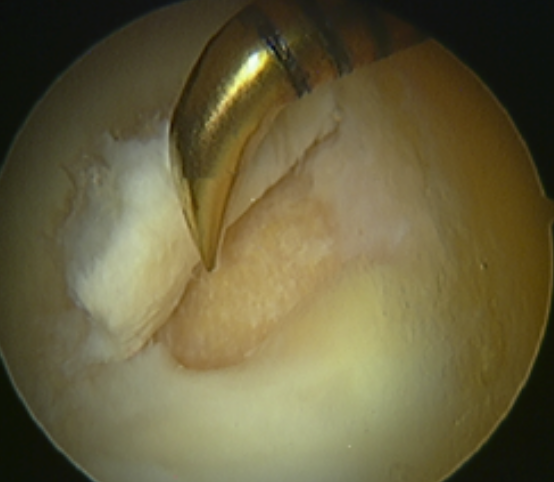

Depending on the type of tear, the labrum may be either trimmed (debrided) or repaired. Various techniques are available for labral repair, mainly using anchors, which may be used to re-stabilise the labrum against the underlying bone, allowing it to heal in position.

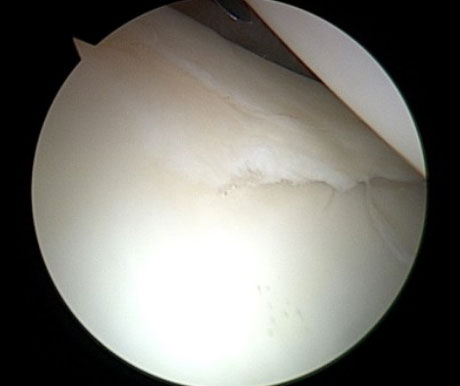

LABRAL TEAR

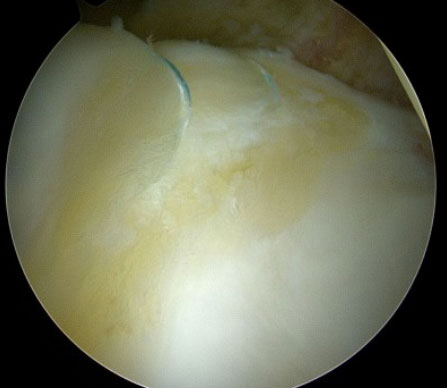

LABRAL REPAIR

STEM CELL THERAPY

There is increasing interest regarding the use of stem cells and other biologics in hip preservation surgery to enhance tissue (specifically cartilage) recovery and repair.

There are many different new techniques available, although many as yet have not been shown to have conclusive long-term benefit. One reason for this is that these are very new techniques and therefore long-term data on its efficacy is not available.

The range of stem cell therapies for cartilage defects ranges from microfracture, (which has been used for many years now and does have reasonable results), to bone marrow stem cell soaked collagen patch grafting (with or without the use of fibrin adhesives). All of these techniques are designed for use in treating small, defined cartilage defects in joints that do not have generalised arthritis or degenerative change. The short-term results in this scenario are quite good.

However, with the increasing burden of younger patients with hip problems, the demand for stem cells as an adjunct to joint preserving surgery is going up. The problem is that stem cell therapies are increasingly being used to try and treat generalised arthritis, as a last ditch attempt to avoid a hip replacement. Unfortunately, the results in this scenario are generally poor.

Mr Stafford has a range of options available, including those described above. However, be aware that, with the exception of microfracture, these techniques attract a premium, which currently will not be covered by your insurance.

REHABILITATION

The patient may need crutches for a short period post-operatively, but as soon as they are comfortable enough to walk without they may be discarded. This is usually within a week or so. Depending on the job, we usually suggest two-weeks off work and then a gradual return, initially trying to avoid rush hour for a week or so.

Gentle stretches and non-impact exercises such as cycling are encouraged from the outset to get the muscles working properly and reduce the risk of scar tissue forming in the joint. The patient may swim as soon as the stitches have been removed and the portals are healed and dry. The patient then engages in the post-operative recovery program, which lasts for four months in total. Impact exercises are discouraged until the three-month mark to allow healing inside the joint and to discourage any persistent muscle inflammation that can occur.

RESULTS

There are increasing levels of evidence that hip arthroscopy is an effective method of treating many conditions. It is not, however, guaranteed. As a general rule we usually say that at the one-year mark post-operatively, 80% of patients will feel the operation has worked, 15 % may feel no change and unfortunately 5% may feel that their symptoms have worsened.

Improvements in post-operative imaging techniques such as MRI cartilage mapping twinned with 3-dimesional CT reconstructions of the hip do now give us an excellent indicator to who may benefit the most, and can help us give advice as to whether you are suitable.

HIP ARTHROSCOPY FAQs

We would advise taking the rest of the week off, and then work from home the following week – if possible. We would advise avoiding rush hour during the third and forth week post op.

10 – 14 days post op. This will be carried out during your follow up consultation with Mr Stafford. He will also take your stitches out personally.

A physiotherapist at the hospital will see you after surgery and will give you some exercises which you can do when you are home. We would then advise seeing a physiotherapist again around 7-10 days afterwards.

Recommended Physio: 12-15 sessions over 3-4 months

It takes typically 2-3 days to walk without crutches.

Around 3-4 weeks after surgery if necessary, we would advise 6 weeks for long distance journeys. You can normally drive safely when you are able to carry out an emergency stop and when you are off crutches. If you have had a left hip arthroscopy and drive an automatic car you can drive after a week.

RECOGNISED BY ALL THE MAJOR INSURERS